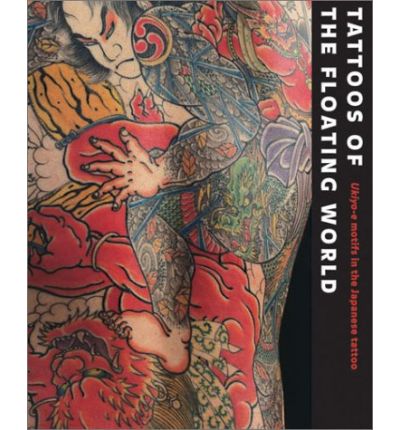

Tattoos of the floating world, Traditional Japanese Tattoo, Tattoos, Love and the Edo Period

Kitamura, though touching inevitably upon the iconography of religion and passion, is more interested in the links between tattoo art and woodblock printing, and the manner in which the Edo period tattoo reflected popular tastes, the arts and Buddhist-inspired concepts like ukiyo (a notion that yoked beauty with impermanence). Flesh -- matter that blossoms and then decays -- is arguably the perfect canvas on which to represent the idea of ukiyo, the transience of things. There is nothing, after all, more perishable than flesh. Dulled, wrinkled and smudged, a skin-print that endures for half a century or more begins to look like the wall of an ancient tomb; traces of figures and outlines become increasingly less visible with the passage of time.

The popularity of artists who depicted the figures of tattooed actors, courtesans and gods, and whose work had enormous appeal at all social levels, coincided with the dissemination of tattoo art among the plebeian masses.

As the woodblock print gradually acquired more color and complexity of design, so the motifs and pigments used in tattooing grew more ambitious and subtle. Kitamura explores the close relationship between these two popular arts. The text is complemented by lush illustrations from ukiyo-e (woodblock print) artists such as Kunisada Utagawa, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi and Toyahara Kunichika, all tellingly juxtaposed with contemporary tattoo images.

Despite the state-of-the-art electric equipment used by all but a few traditionalists and fees that would scandalize the plebeian masses of Edo, tattoos continue to remain living documents, transmitting and codifying colorful elements from the popular culture of the past. It would be a great pity to see them vanish under the pressure of conformity. The only way to avoid that perhaps is by conferring, as this creditable book attempts to do, a little more respectability on the art. The fact remains, though, that you would be more welcome in a Japanese public bathhouse wearing a necklace of shrunken skulls than a tattoo.

:: Buy Tattoos of the Floating World